History

Welcome, Be sure to click on the underlined white links or "Dig Deeper"- updated often!

Welcome, Be sure to click on the underlined white links or "Dig Deeper"- updated often!

Welcome, Be sure to click on the underlined white links or "Dig Deeper"- updated often!

Welcome, Be sure to click on the underlined white links or "Dig Deeper"- updated often!

Welcome, Be sure to click on the underlined white links or "Dig Deeper"- updated often!

Welcome, Be sure to click on the underlined white links or "Dig Deeper"- updated often!

Ok, We built a town, Now what?The birth of the vigilante

THE REAL VIRGINIA CITY & VIGILANTE HISTORY (UNFILTERED)

Who will protect us?

Vigilantes in the American West were individuals and groups who, in the absence of sufficient legal authority, enforced their own brand of justice, often through public trials and lynchings. Their actions, such as those by the San Francisco Committee of Vigilance in the 1850s and the Montana Vigilantes in the 1860s, were a response to rampant crime, corruption, and general lawlessness during the Gold Rush era. While many communities viewed vigilantes as necessary protectors, their methods raised questions about justice and due process, with punishments often being brutal.

Motivations for Vigilantism

Lack Of Order

In remote areas like the mining camps of Nevada & Montana, territorial law enforcement and courts were often weak or nonexistent, leaving communities vulnerable to criminals.

Corruption and injustice

Vigilante groups formed in response to government corruption and cases where the formal legal system failed to punish criminals or protect citizens.

Corruption and injustice

Some groups were driven by a community's desire for order and safety, believing that vigilante action was the only way to prevent further crime and protect their communities from lawless elements.

Examples of Vigilante Groups and Incidents

Montana Vigilantes (1860s):

These groups, centered in areas like Bannack, Alder Gulch, and Fort Benton, targeted "road agents" and other criminals, holding public trials and carrying out swift executions, such as the hanging of George Ives.

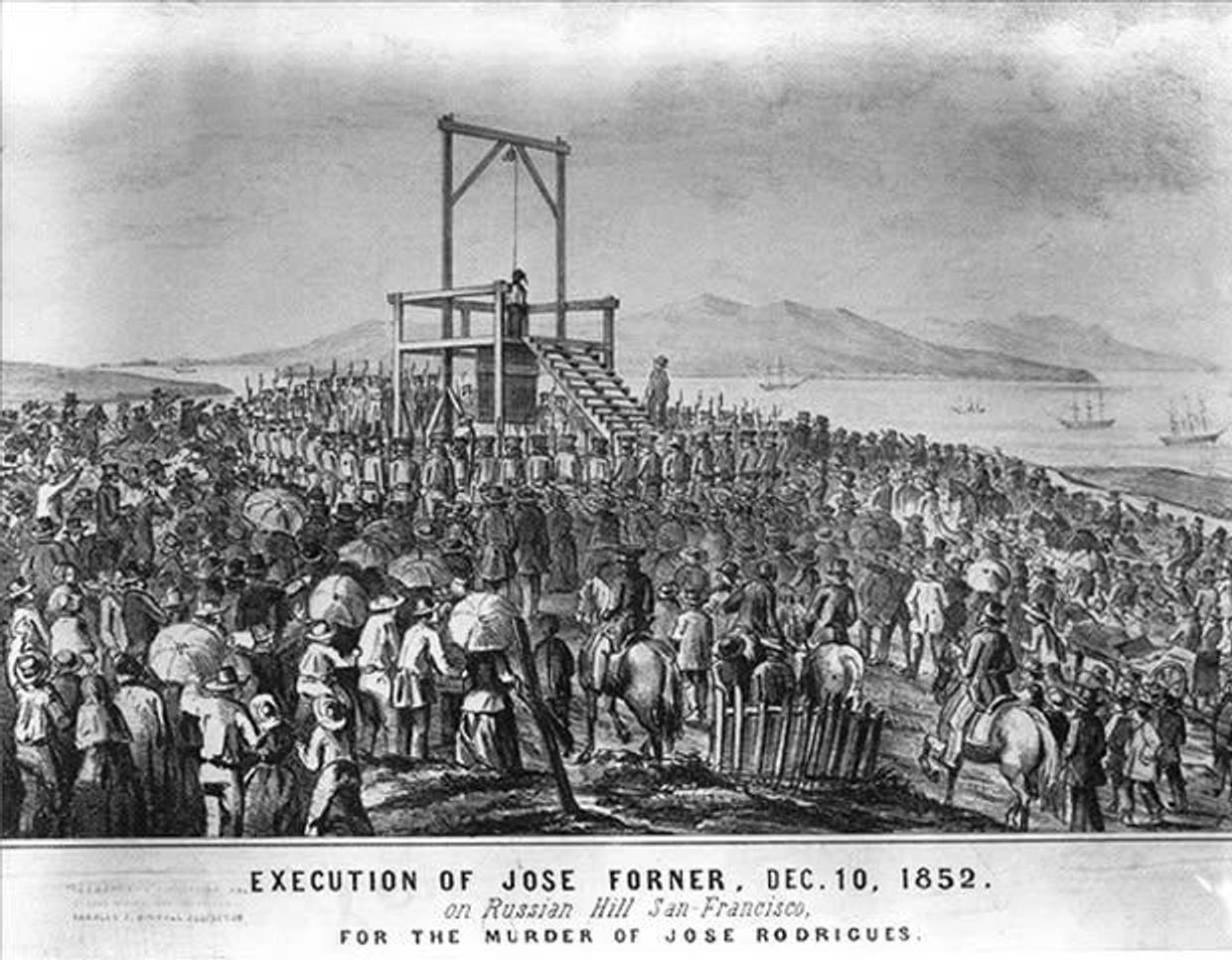

San Francisco Committee of Vigilance (1850s): .

In response to crime and corruption during the Gold Rush, these groups used force to punish criminals, before eventually disbanding.

The Bald Knobbers:

A powerful group in Missouri, they formed to combat crimes like murder and robbery that were going unpunished, but their actions eventually led to violence, necessitating intervention from the governor.

Methods and Consequences

Public Trials and Executions:

Vigilantes often held public trials and swiftly executed those found guilty, with hangings being a common form of punishment used as a deterrent.

Brutal and Arbitrary Justice:

While often seen as necessary, their methods were brutal and often lacked the formal legal safeguards of due process, leading to both swift outcomes.

Community Support and Opposition:

While some residents supported vigilantes for providing essential protection, their power sometimes led to abuse, resulting in opposition that eventually led to the collapse of some movements.

“Necessity is the Mother of Invention”

The western frontier was often a dangerous and lawless place. When justice needed to be served, there wasn't always a Sheriff and Judge available...or willing.. Instead, there were honorable and righteous men and women who stepped in to dispatch swift justice. These groups were known as Vigilance Committees and they existed across the west.

Law & order was scarce on the frontier, citizens often formed these "Vigilance Committees" to keep an eye on the community, to deal with problems and crime. When a problem arose, the Silent Riders would mount up and discreetly spread the word to other members that help was needed. Using this approach, members could remain largely anonymous to the general public and not cause a panic. Here are examples of Virginia City Old West Crime.

Vigilante Justice in Mining Camps

In the silver & gold camps, hundreds of men lived and worked side by side, fearing that the gold they found might be stolen. When they discovered a thief they often created ad hoc courts, heard the evidence, and dealt summarily with the offender. The punishment was usually flogging or banishment, but if the offense was more serious, the offender was hanged. Thus began an era of vigilante justice in the American West.

Even so, the mining camps moved as quickly as they could to formalize legal institutions, create courts, and elect sheriffs. Travelers who were impressed by the presence of guns were also impressed by how men from back East had brought with them the civic and democratic traditions of their homes.

At the camps and in the port city of San Francisco, whose population was also growing at breathtaking speed, vigilante justice was also popular at first. Newspaper editors supported it as the necessary response to what would otherwise be chaos and brute force. They also appreciated the fact that it saved the nascent community a lot of money and time.

The speed and ferocity of vigilante punishments were designed to have the strongest possible deterrent effect. For example, an Englishman named James Stuart traveled from Australia —which was then the site of a large British penal colony— to the gold rush camps of California. He was suspected of a series of thefts, and then of killing a merchant in 1851. The San Francisco Vigilance Committee seized him; it was organized by Sam Brannan, a Mormon businessman and one of the wealthiest men in the city. Hundreds of supporters of the committee poured into the streets as news spread of Stuart’s arrest.

The local sheriff, lacking manpower to take the accused villain away from the vigilantes, made a feeble and ineffective protest before Stuart was marched down to the harbor and hanged in public. California’s governor approved of the action. When an indignant judge impaneled a grand jury to indict the ring leaders, it refused to do so; several of its members belonged to the Vigilance Committee.

A few weeks later the Committee attacked the city jail, seized two other men, and hanged them both, despite the authorities’ attempts to protect them. The committee abolished itself after three months out of deference to due process, but reconvened in 1856 and undertook four more lynchings, again with a high degree of popular and press support, public demonstrations, and pseudo-military regalia.

This is a transcript from the video series The American West: History, Myth, and Legacy.

Virginia City, Nevada

1800's

Looking North

Built By Hands

...And Still Standing

Virginia City, Nevada, emerged as the epicenter of a significant mineral discovery in the Western United States known as the Comstock Lode. This valuable ore deposit, which became the single most lucrative find in the region, was brought to light in 1859 by Irish immigrants James McLaughlin and Peter O'Riley. Their exploration led to the revelation of the Comstock Lode's existence at the location that would later develop into the town of Gold Hill, situated adjacent to Virginia City.

Although the pivotal event occurred in 1859, the area surrounding the Comstock Lode had been subject to placer mining by several hundred miners for years before the discovery. Ironically, these miners struggled to make a living, unaware that a few miles away lay the richest ore discovery in history, with numerous exposed outcrops waiting to be found.

The soil in the vicinity contained a dense blue mud that complicated the separation of gold. Eventually, a sample of this distinctive mud underwent assay testing, revealing astonishing results – hundreds of dollars of gold and thousands of dollars of silver per ton. This revelation triggered a rapid dissemination of the news, sparking a stampede to the Comstock Lode.

Prospector Henry Comstock, characterized more as a smooth-talking individual than a genuine miner, cunningly affixed his name to the discovery by duping the Irish miners into signing a portion of their claim over to him.

The mines of the Comstock elevated Virginia City to the status of a prosperous frontier town. Despite its challenging location on the side of Mount Davidson, the town offered all the amenities of San Francisco, ranging from fresh oysters and fine whiskeys to the latest Parisian fashions for women.

In the early 1860s, Comstock miners earned one of the highest industrial wages globally – $3.50 per day.

Virginia City boasted over 100 saloons, each striving to distinguish itself in a competitive market. Some saloons even featured indoor shooting galleries where patrons could enjoy a few drinks while taking aim at targets.

The city faced a notable challenge with its notoriously poor water quality from the mines beneath it. In the early 1870s, a groundbreaking water system was developed to transport water from the Sierra Nevada mountains to Virginia City. Comprising over 20 miles of flumes and pipes, this innovative water system continues to operate more than 150 years later.

In 1875, disaster struck Virginia City in the form of "The Great Fire," a wind-fueled inferno that devastated the city and left up to 10,000 residents homeless. Typically, such an event signals the decline of prosperity for a frontier town. However, Virginia City defied the odds by undertaking an extensive rebuilding effort with no expense spared, solidifying its position as the world's most prosperous mining camp.

You Can't Re-write history

A sensitive but necessary subject-By Janice Oberding

I'm a historian, some of my favorite topics to research are crime and ghosts...History isn't always easy to look at--but look, we must. In that vein with all the recent talk of lynchings I gathered some of my notes on lynchings. Granted lynching in the west was vastly different than that of the Southern US, still I do not see how any caring, thinking human being could have turned a blind eye to, much less condone, such behavior.

A Brief History on Lynchings in the West

Hundreds of people have been lynched throughout Western history. Many of these involve a group of people taking the law into their own hands (vigilantes) breaking into a jail and removing someone they believe is guilty, taking that person out and lynching them before they’ve been given a fair trial. According to the late Nevada historian Philip Earl “Vigilante justice was one of the most intractable problems which faced early day law enforcement officials.”

The lynching of Josefa Segovia was different in that she received a mock trial. Josefa, a Mexican woman, is the only woman to have been lynched in California. In the mock trial Josefa was found guilty for the murder of Frederick Cannon and lynched from the Jersey Bridge on July 5, 1851. Incidentally, Daniel E. Hungerford, the father in law of John Mackay was involved with the event.

In November 30, 1858 gang member Pancho Daniel was in jail and awaiting trial for the murder of Los Angeles County Sheriff, James Barton. A group of men broke into the jail, pulled Pancho Daniel out and lynched him on a jail gate. Although a reward was offered, no one was ever arrested for the crime.

The 1871 Los Angeles Chinese Massacre involved fifteen Chinese being lynched in what is believed to be the largest mass lynching in US history.

In the summer of 1892 in Redding California two outlaw brothers, Charles and John Ruggles were in jail and awaiting trial for robbery and murder. Their trial date was set for July 28th1892. Four days before that trial was set to take place a mob of masked men broke into the jail, took the Ruggles brothers out and lynched them. No one was ever prosecuted for the lynching.

On December 5, 1920 suspected murderers Terrence Fitts and Charles Valento were taken from the Santa Rosa jail and lynched.

April 22, 1902 a group of masked men broke into the jail at Skidoo and demanded Joe Simpson, awaiting trial for murdering James Arnold, be turned over to them. Fearing for his own safety, the guard handed over the prisoner who was then taken to a telegraph pole and lynched.

A more modern day lynching took place in California on November 26th 1933. Suspected kidnap/slayers Thomas Thurmond and John Holmes were pulled from their San Jose jail cells by a mob of over 6,000 people and lynched. The California governor approved the lynching saying he would pardon anyone involved.

Of Oregon’s twenty-one lynchings, Alonzo Tucker is the only black man in the state’s history to be lynched. On September 18, 1902 Tucker an African American man was lynched from a bridge in Marshfield (which is today Coos Bay.) Gymnasium owner and boxer, Tucker was innocent but a mob lynched him on the word of one person.

In Nevada, no black person has ever been lynched. This does not make lynching any less nefarious. The following are some of the lynchings that have taken place in the Silver State.

In Belmont Nevada June 4, 1874 two miners, Jack Walker and Charlie McIntyre suspected of murder and other criminal acts, were lynched by vigilantes.

August 7, 1864 a group of vigilantes pulled James Linn from his jail cell in Dayton where he was awaiting trial for the murder of John Doyle. Linn was lynched there on the street.

In Reno Nevada a Winnemucca ranch hand by the name of Luis Ortiz was in the Reno jail for murdering Constable Nash. An angry mob broke into the jail, took Ortiz to the downtown bridged where he was lynched on September 17 1891. Three days after Ortiz’ lynching Constable Nash made a full recovery.

In Genoa, Nevada the tree where Adam Uber was lynched still stands. On the night of December 7, 1897 Adam Uber was in a Genoa jail cell awaiting trial for the murder of Hans Anderson. A masked mob broke into the jail and pulled Uber down Boyd Lane where he was lynched. After he was dead, the mob shot at and defiled the body. According to legend, Uber placed a generational curse on those who lynched him. Some of those involved in his lynching either died horrible deaths or saw members of their families die violent deaths.

Richard Jennings lost his temper and sealed his fate when he shot and killed John A. Barrett, a popular Austin rancher, after a brief argument at the International Hotel. While awaiting trial, Jennings was taken out of jail by vigilantes and lynched at the courthouse on December 14, 1881.

Hazen Nevada was so proud of its lynching of Red Wood in February 27, 1905 that it dug up the dead man’s body and re-hanged it on a telephone poll so that newspaper men could get a good photo of the hanging. What was Red Wood in jail for? He was in jail for robbery.

December 1875--In Carson City arsonist Tom Burt was ordered to leave town by the 601 Vigilantes. When he refused to do so, Burt was lynched at the cemetery gate.

Two men were lynched in Virginia City: they were Arthur Perkins (Hefferner) and George Kirk.

On March 4, 1871 Arthur Perkins stopped in at the saloon in the International Hotel. For whatever reason, he felt that Bill Smith had insulted him too harshly. So he shot and killed Smith. He was arrested and taken to jail. But this did not satisfy the 601. During the predawn hours of March 5, the vigilantes broke into the jail, grabbed Perkins and pulled him to a secluded spot where he was quickly lynched. His lifeless body was discovered hours later. A note was pinned to his coat that read, Arthur Perkins--Committee No. 601

When the 601 ordered fire bug George Kirk to leave town he pretended to do so. But he returned. And that was a big mistake. The 601 took him to a quarry and lynched him.

1800's Virginia City

Dusty Dirty & Muddy Streets of Virginia, Nevada Territory

The Perfect Setting for The Birth Of A Historical Town

Virginia City, Nevada by Kathy Alexander

A once-bustling mining town in the late 1800s, Virginia City,Nevada was heralded as the most important settlement between Denver, Colorado, and San Francisco, California, in the time of its heydays.

One of Nevada’s oldest settlements started when two miners by the names of Pat McLaughlin and Peter O’Reilly discovered gold at the head of Six-Mile Canyon in 1859. Soon, another miner named Henry Comstock stumbled upon their find and claimed it was on his property. The gullible McLaughlin and O’Reilly believed him, which assured Henry a place in history when the giant Comstock Lode was named.where they are.

However, the Comstock Lode would not be known for gold but rather for its immensely rich silver deposits. Though silver had initially been discovered in 1857 in Nevada by brothers Ethan and Hosea Grosh, they died before recording their claims. Though the miners rushed in after discovering gold, they could not get to it because of the heavy blue-gray clay that clung to picks and shovels. However, when someone had the good sense to assay the sticky mud, it was found to be worth $2,000 a ton – a very nice amount in those days.

Word of the discovery spread like wildfire and lured California gold miners in a reverse migration back over the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range. Within no time, a ramshackle town of tents and shacks was born. When a miner named James Finney, who was more often called “Old Virginny” from his birthplace, dropped a bottle of whiskey on the ground, he christened the newly founded tent-and-dugout town “Old Virginny Town” in honor of himself. It was later changed to Virginia City. By 1862, the population had soared to some 4,000 and would continue to increase over the next decade and a half.

Grubby prospectors became instant millionaires. Famous men like William Ralston and George Crocker found the Bank of California; Leland Stanford, George Hearst, John Mackay, and William Flood made their fortunes in Comstock mining. Soon mansions, imported furniture and fashions from Europe, and the finest in food, drink, and entertainment were commonplace. Virginia City quickly rivaled San Francisco in size and excess.

All the new wealth caught the eye of President Abraham Lincoln, who needed gold and silver to pay Civil War expenses, and on March 2, 1861, Nevada became a territory. Statehood came just three years later, on October 31, 1864, even though it did not contain enough people to constitutionally authorize statehood.

In Virginia City, Samuel Clemens, then a reporter on the local Territorial Enterprise newspaper, first used his famous pen name of Mark Twain. He went to work for the newspaper in the summer of 1862 at the age of 26. A year later, he began signing the name “Mark Twain” to his columns.

Engineers made amazing breakthroughs to facilitate the silver removal. New honey-combed, square-set timbers became the industry standard to shore up mine shafts.

Water pipes were stretched from the Lake Tahoe Basin to provide over 2 million gallons of fresh mountain water daily. A four-mile-long tunnel was blasted from solid rock by Adolph Sutro to drain over 10 million gallons of boiling, rancid water per day from the lower levels of the mines.

For the miners working the Comstock Lode, it was extremely dangerous as they faced cave-ins, fires, and underground flooding. The water temperature and deeper levels would rise to more than 100 degrees, and often when miners penetrated through rock, steam and scalding water would pour into the tunnel.

In 1869 William Sharon and William Ralston built the Virginia and Truckee Railroad to haul ore from the Virginia City mines to the ore mills along the Carson River in the valley below and east of Carson City. Known as “the crookedest railroad in the world” due to its dizzying descent of 1,600 feet in 13 miles, the railroad would then return with wood and supplies to Virginia City

By the 1870s, over $230 million had been produced by the mines, and Virginia City continued to grow. At the peak of its glory around 1876, Virginia City was a boisterous town with many businesses operating 24 hours a day.

At that time, the boomtown sported some 30,000 residents, 150 saloons, at least five police precincts, a thriving red-light district, three churches, hotels, restaurants, ten different fire departments, its own water, electric, and gas systems, and numerous other businesses. The thriving community also provided various types of entertainment, including Shakespeare plays and dances at Piper’s Opera House, which continues to stand, as well as opium dens, dog fights, and more than 20 theaters and music halls. Its International Hotel was six stories high and boasted the West’s first elevator, called the “rising room.”

But like other mining boom towns, Virginia City would eventually begin to decline, beginning in 1877. From the time it was first established through its decline, Virginia City suffered five widespread fires, the worst of which was dubbed the “Great Fire of 1875,” which burned nearly 75% of the town and caused some 12 million dollars in damages. But the residents persevered, and the town was rebuilt in about 18 months.

The Comstock Lode was thoroughly mined by 1898, and the city once again took a sharp decline. From 1859 to 1919, more than 700 million dollars in gold and silver were taken from the mines of the Comstock Lode, which mines’ were excavated to as much as 3200 feet. By 1920, there were just a few small operations in business, and by 1930, only about 500 people lived in the community.

Today, the historic community is a National Historic Landmark, designated as such in 1961. It now boasts about 1,000 residents, and though a shadow of its former self, it draws more than two million visitors per year. Numerous historic buildings continue to stand, including Piper’s Opera House, which still entertains customers today, and the Fourth Ward School, built in 1876, is utilized as a museum. Numerous mansions also continue to stand, which provides visitors with the sophisticated and lush lifestyle of these long-ago residents. The Virginia & Truckee Railroad runs again from Virginia City to Gold Hill. The landmark is the largest federally designated Historical District in America maintained in its original condition. “C” Street, the main business street, is lined with the 1860s and 1870s buildings housing specialty shops, restaurants, bed and breakfast inns, and casinos.

As a federally designated National Historic District, it is illegal to dig for artifacts, remove any found items from the community, or mistreat any property.

Virginia City is located about 23 miles south of Reno, Nevada

Densely Populated

Virginia Township, Nevada

Virginia City grew overnight becoming a vastly populated community, all compacted into a small 544 acre ares or 0.87 square miles.

Although this was a genuinely peaceful town (except for the sound of stamp mills crushing rock throughout the day) This small city had all of the issues a largely populated city had, such as occasional robberies, public fights / drunkenness , theft etc. The need for constabulary support was deemed necessary, hence... the Vigilance Committee was established.

Vigilantes Performed Popular, Yet Violent, Public Service

The states and territories of the plains and mountain West showed comparable patterns of vigilante justice. While miners feared that the gold dust they were painstakingly accumulating might be stolen, cattlemen had to be vigilant against the threat of horse and cattle thieves. Theodore Roosevelt expressed a fairly common opinion when he wrote that in the early days of these ventures, that vigilante justice and even vendettas, were defensible.

“As soon as the communities become settled and begin to grow with any rapidity, the American instinct for law asserts itself; but in the early stages each individual is obliged to be a law unto himself and to guard his rights with a strong hand.”

— Theodore Roosevelt

1863, the remote community was plagued by a gang of hijackers who attacked gold convoys and stagecoaches, seizing property and killing travelers. The citizens and those of the nearby settlement created a vigilance committee of their own, only to discover that the criminal mastermind was their own sheriff. He was an odd, many-sided character, extremely hot-tempered, who over the years had shot and killed several men in barroom brawls.

By Patrick N Allitt, PHD- Emory University

Old West Vigilantes

In the Wild West, where the law was often non-existent, Vigilantes often took “enforcement of the law” and moral codes into their own hands. The term vigilante stems from its Spanish equivalent, meaning private security agents.

Vigilantes were most common in mining communities but were also known to exist in cow towns and farming settlements. These groups often formed before any law and order existed in a new settlement. Justice included whipping and banishment from the town, but offenders were often lynched. Sometimes, however, vigilante groups formed where “authority” did exist but where the “law” was deemed weak, intimidated by criminal elements, corrupt, or insufficient.

The vigilantes were often seen as heroes and supported by the law-abiding citizens, seen as a necessary step to fill a much-needed gap.

Though this was usually the case, sometimes the vigilance committee began to wield too much power and became corrupt. At other times, vigilantes were nothing more than ruthless mobs, attempting to take control away from authorities or masking themselves as “do-gooders” when their intents were little more than ruthless, or they had criminal intent on their minds.

The San Francisco vigilantes hung James Casey and Charles Cora.

One of the first vigilante groups formed was the San Francisco Vigilantes of 1851. After several criminals were hanged, the committee was disbanded. However, when the city administration became corrupt, a vigilante group formed again in 1856.

Hundreds of these groups were formed in the American West, such as theMontana Vigilantes, who hanged Bannack Sheriff Henry Plummer in 1864. Controlling the press, the sheriff was made out to be the leader of an Outlaw Gang called the innocentss.

However, history now questions if it wasn’t the vigilante group who was behind the chaos in Montana and that Henry Plummer was, in fact, an innocent man.

Following the Civil War, the Reno gang began to terrorize the Midwest, forming the Southern Indiana Vigilance Committee. The next time the Reno Gang attempted to rob a train, a vigilante group lynched its leaders – Frank, William, and Simeon Reno.

Tales like these abounded throughout the Old West as numerous vigilantes attempted to tame the lawless frontier.

© Kathy Alexander

John Daly and the Vigilante Justice Committee

John Daly was born in New York. As a young man, he migrated to California. Leaving a string of dead men behind him, he then went to the gold mining town of Aurora Nevada The mining company and the town fathers were looking for someone to protect their interests from the criminal element. Since Daly carried himself well, and seemed to know how to handle a gun, they hired him as a deputy city marshal. No one ever thought they would one day need a vigilante justice committee.

Daly convinced everyone that he needed some policemen to help him, so he hired Three Fingered Jack, Italian Jim, Irish Tom and a couple of other men who seemed to be of questionable character.

In a short time, the men augmented their income by shaking down the local merchants. Also, people who protested ended up in the local graveyard.

Finally, one of Daly’s policemen attempted to steal a horse from a local merchant by the name of William Johnson. In the process, Daly’s man was killed. It took a few months, but on February 1, 1864, Daly and his associates made an example of Johnson. He was clubbed, shot in the head and his throat cut.

The honest citizens had looked the other way long enough. They formed the Citizens Protective Order, which is a fancy phrase for a vigilante justice committee. Daly and his gang were arrested and jailed. For a short time…a very short time, if seems as if the men were going to be tried before a judge and jury. But on February 10 the Citizens Protective Order the gang out of jail, escorted them to a scaffold, and ended the whole affair right then and there.

This action angered Governor James W. Nye so much that two days later he headed for Aurora with a Provost Marshal Van Bokkelen and United States Marshal Wasson and was going to call out the troops from Fort Churchill to put down the vigilantes. After the Marshal looked into the facts, no action was taken against what was now called the “Citizen Safety Committee.”

Q: What exactly is vigilante justice?

Vigilante Justice, sometimes called frontier justice, is the enactment of retribution by a person or group of people who claim they have been wronged yet lack of authority to enact justice.

Q: Why did vigilantes appear in the American mining towns?

Vigilantes took the law into their own hands as most of the American Mining Towns were in remote areas out of reach of the law of the land.

Q: Was vigilantism illegal in the American west?

Vigilantism was often tolerated in the mining towns of the American West, but when government was involved, they could be tried for their actual offenses, not merely vigilantism itself at the time.

Q: How did vigilantism help the miners of the American west?

The Vigilantes of the American wild west usually formed as a committee. They would enact justice in the place of an absentee government. It was rare to have the solitary Hollywood hero as the numbers were against them.

-Dakota Livesay

Play Stupid Games, Win Stupid Prizes

_________________________________________

"You are free to choose, but your choice is not free from consequences" -a wise man

Fun Fact

Not Just Silver

In June of 1859, one of the most significant mining discoveries in American history was made in the Virginia Range of Nevada. The discovery of gold in the area drew people in from across the country.

Virginia City Silent Riders

Virginia City, Nevada, United States of America

Cookie Policy

This website uses cookies. By continuing to use this site, you accept our use of cookies. They taste good as well!